Figure #1.

Rope Descent System (RDS) and boatswain’s chair – stepping over the roof edge is psychologically the toughest moment.

How many architects does it take to change a bulb?

I have among my clippings an article titled “Whose bright idea?” The title hints a designer’s responsibility for a dysfunctional façade access at the Secaucus train station of New Jersey Transit. The seemingly simple task of changing a light bulb is described as a painstaking ordeal requiring use of two cranes: one lifting another through a hole cut in a roof at the expense of tens of thousands of dollars. The architect explained the façade access was sacrificed on altar of a subjectively perceived beauty: a desired dramatic visual effect of a skylight void of any unsightly obstructions.

I am sure no architect would like to become a subject of the front-page, innuendo attack of this kind but I must admire his civil courage to admit the responsibility. Architects are quick to deny any responsibility for a workplace safety. It’s also my experience that architects generally don’t like industrial look associated with the means of access and keep them out of the drawings in an act of denial, successfully sabotaging design coordination.

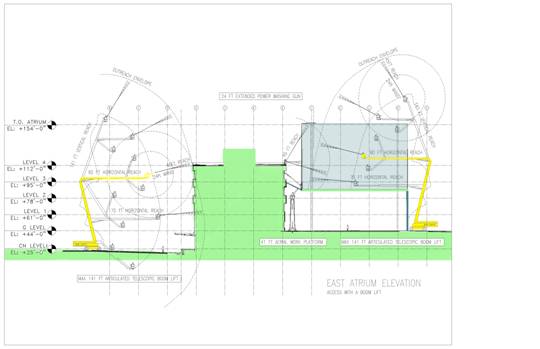

Figure #2.

Aerial platforms afford greatest flexibility but they reach limited heights.

Cost of access

Another story: I was recently involved in an investigation of 13 irreparably damaged glass panes in two adjacent, brand new residential apartments. Glass replacement was estimated at $650K. That’s right: $50K a piece. It’d not be fun to be assessed over $300K for a glass replacement in your apartment.

Was the glass covered with a layer of a precious metal to justify the elevated cost? Yes, it was, just like any regular, off the shelf, low-E glass. Therefore, the coating was not the reason for a high cost; actually, the material accounted for only 7% of the total cost.

The process of glass replacement required use of a 120ft hydraulic truck crane in addition to the brand new building maintenance unit (BMU) installed on the roof. The use of a truck crane would require negotiations with the city to close a busy street for traffic and it would need to happen at least twice, because of the curing time of a silicone sealant. The expensive house crane not only had insufficient reach, but also indirectly contributed to the glass damage problem. The weight of the BMU (being essentially a roof crane) was not initially calculated into the building structure. The structure of the roof slab was remedially strengthened to carry loads from the BMU after the top floor was already closed. The weld splatter generated by the heavy construction operations irreparably damaged glass throughout the top floor. This is how costly a lack of coordination of design and planning of façade access may turn out to be.

In its 2000 study National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH) reported 8102 fatal falling accidents in a 14 year period, with majority

attributed to building construction. Falls were identified as a leading cause of

occupational fatalities by National Traumatic Occupational Fatalities (NTOF).

Roofs, scaffolds, and ladders were identified as the most dangerous locations.

In its 2005 study, U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) listed 246,810 non-fatal

working fall accidents in the year 2004 alone. |

The minimum requirement of façade access safety

My experience is the architects seldom make the conscientious choice with regard to façade access. Reason? The requirement is absent from most building codes: it comes via the back door in form of federal regulations protecting rights of the façade users (in a similar way as persons with disabilities were protected indirectly by an Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) for a long time before the requirements found its way into the codes).

However; it doesn’t mean that architects are not responsible for the compliance. A standard AIA Owner-Architect agreement states that “the Architect shall review laws, codes, and regulations applicable to the Architect's services. The Architect shall respond in the design of the Project to requirements imposed by governmental authorities having jurisdiction over the Project.”

The requirements are listed in Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA) and the standard ANSI/IWCA I-14.1 “Window Cleaning Safety.” IWCA stands for International Window Cleaning Association. Some jurisdictions implemented their own sets of requirements – New York City for example.

OSHA is a regulatory law and its broad scope covers, among others, fall protection, walking surfaces, descent equipment, scaffolding, and powered platforms. The Window Cleaning Safety Standard is referenced in a common law and specifically covers safety of window cleaning operations.

A worker is protected by Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) against the hazard of working on a roof, façade, or their appurtenances that are not properly equipped and adapted to assure his/her safety. The responsibility to adapt the building is on the part of building owners, managers, and their agents. The building’s owner should be able to exhibit pattern of due diligence; this usually entails having a plan of service, fall protection anchorage periodically engineered and certified, and demonstrating the compliance to out-of-house contractors prior to work.

Another story. I was inspecting the existing facade of a prominent news headquarters station located in Atlanta, GA following the 2008 tornado. I was standing on a swinging scaffold outboard of the wall of the building, when a large coil of a steel rope fell down unrolling and almost killing me in the process. Fortunately I wasn’t injured. A worker who rigged the system admitted to me that he had only three months worth of experience and zero training in the construction industry.

This experience of mine was not alone; I sustained similar safety accidents before and they makes me believe the general level of upkeep of the façade access equipment and employee training is seldom subject to scrutiny because of its infrequent use. A periodic due diligence assessment, annual engineer’s re-certification, and crew scaffold training are not only indispensable risk management tools in a building’s manager defense arsenal but also they may save lives.

In a hypothetical situation if I were injured, I might sue the manager, the owner, and the contractor who were the parties responsible for my wellness. I would point out to the negligence and cite the OSHA standard. They, providing found negligent by a court or settled before trial, would turn to their insurance carriers to cover the bill after their policy deductible has been exhausted.

Another story. Beware prospective buyers of high-rise buildings. I recently inspected a 500+ft tall tower that was falling in disrepair. The cladding was earlier deemed structurally unsafe and the davits on the façade weren’t inspected for decades. The façade contained a number of deep overhangs and the davits were installed at the underside of the rusting steel structure behind suspended soffits. (Figure #3) How to inspect a façade like this? First, hire a Spiderman, who would need to scale the façade and inspect the integrity of the davits, which in turn would require a partial demolition of soffit cladding to uncover their points of attachment. Another option would be to hire an engineer and design and build a new system of davits independent of the old ones just to reach the old ones. Scarcity of Spidermen on the market makes their services prohibitively expensive. Therefore, at least one new system of davits would be required to provide access to sites of the target davits.

Figure #3.

Spiderman’s challenge – façade access under massive overhangs.

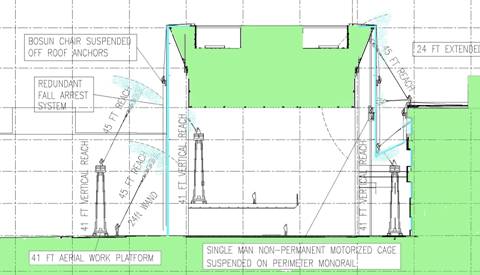

Figure #4.

By far the most popular means of access is a motorized swing stage.

Design of a new high-rise building

An architect should inform the owner of the need early enough, explain all ramifications, and ask to have the façade access included in the program to allow for reasonable budgeting.

Theoretically, an owner of a high-rise building may retrofit the façade or roof of a building to allow façade access after the completion. However; there are many factors that make this solution uneconomical and impractical, compared to the integrated design. The strengthening of the structure to achieve the required structural strength of anchor points, interruptions and penetrations of roofing, unsightly modifications of cladding are among them.

As a consultant I often push architects to ask owners questions and naively expect them to come back with an answer. However, a typical question may take several rounds to respond. The one about the desirable solution for the façade access is a good example. An owner typically responds: “Window washing? We don’t plan to wash our windows, even if so, we would hire an out-of-house window washers to do the cleaning.”

The safety of individuals performing work at elevation is a responsibility of the owner and/or building manager. An out-of-house crew is subject to the same rules of gravity as the in-house employee and deserves the same safety measures. A designer needs to educate the owner about safety regulations and propose workable solutions to fit the budget.

Solutions

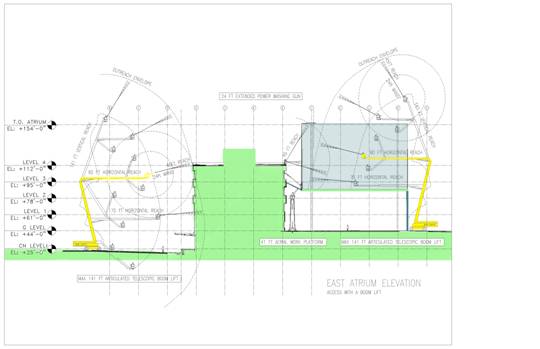

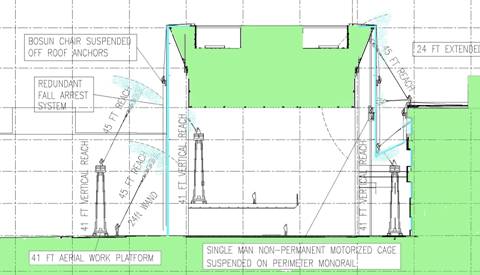

Every design benefits from façade access analyses (Figure #5 and 6). There are several rules of thumb. Redundancy is another word for safety. The primary access system must be doubled by a personal fall arrest system.

All repair work requires materials. Many materials cannot be safely transported by the same means as workers because of limited weight capacity.

Glass is a good example. A single pane of glass may easily weight 1500lbs.

Therefore, a façade would require a tertiary hoisting system to lift the materials in addition to the access system and fall arrest system.

Figure #5.

A façade access study analyses alternative means of access.

Figure #6.

Interior façade access may present a greater challenge than the exterior.

A worker must be provided with a fall restrain system when approaching a distance 6ft from a fall hazard. Skylights and sloped glazing are considered a fall hazard. A façade should be served by a system of roof davits spaced no more than12ft apart to allow support of powered platforms, and the ropes should not turn more than 75 degrees from the façade plan.

A façade stabilization system should be provided on buildings higher than 39.6m [130ft] to restrain movement of the equipment, even though a high-rise building may be successfully served by a road crane.. A simple one would consist of window washing pins spaced 50ft apart, and a sophisticated one would consist of a tie-in guide rail (a mullion track).

Another story. I was inspecting a +700ft tall high-rise façade from a corner swing stage, when a sudden gust of wind swirled the platform 180 degrees, hitting and damaging a curtain wall of the inspected building. The power cables, motor ropes, and lifelines twisted and tied together. This accident would not happen if the façade stabilization system was utilized.

All equipment and anchorage are typically specified as delegated design items, however they need to be properly coordinated with the remainder of the design, most notably with a structure and a water protection layer of roofing.

I typically advise architects in the CD stage to draw a roof plan and coordinate all the necessary components that are likely to be present there: roofing slopes, drains, scuppers, expansion, movement joints, hatches, mechanical equipment with supports, ducts, walls, electrical trays and equipment, antennas, lightning equipment, low-voltage systems, rails, ladders, fall arrest systems, storage zones for heavy equipment, etc.

Roofs are so far away in a construction schedule that I never seen their coordination done. This normally produces a mess on a roof – the very portion of the building that plays the most important role in shielding it from elements.

The most dramatic condition I ever seen in field was a precast concrete plank in a middle of two expansion joints that were erroneously drawn 5ft apart on construction drawings (Figure#7) and produced by contractors with accordance to the drawings. This precast concrete plank is only supported on light-gage metal stud interior walls. The expansion joints were built like that through all the stories up to the roof. How it went undetected for so long? Inspectors employed during the construction phase don’t question design because their job is to compare construction with the design intent, not to question the design. Inspectors who question the design loose their job, as my company did on this project. Too bad for you if you happen to live there because the owner of this apartment building has elected not to remediate this condition. The design errors usually turn out to be too costly to remediate, what explains frequent attempts to hide them by unscrupulous owners and developers.

Figure #7.

Erroneous construction drawings resulted in portions of concrete deck left insufficiently supported between two expansion joints.

Choices

The façade access can be roughly classified as proactive and reactive from a designer’s perspective.

Reactive access measures include all portable equipment: aerial platforms, truck cranes, parapet hooks, counterweighted outriggers, ladders, boatswain’s chairs(Figure #1), supported scaffolds, powered platforms (Figure #2), and others. They typically can be rented out and brought to the site.

Proactive measures include all permanent anchorage and equipment and can be further divided into standard and dedicated systems. Plethora of manufacturers provide standard systems at differing levels of utility: ranging from simple loop davits and guards (Figure #8), to house cranes (Figure #13). The dedicated systems are custom engineered to respond to a challenge created by a specific building: e.g. gantries are almost always custom-engineered specifically for safe access to a specific bridge or a skylight.(Figure #10)

Equipment guides and glossaries are available online e.g. http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/scaffolding/

Figure #8.

42” guard protecting the roof edge and a ladder platform.

Barricades, nets, and sidewalk bridges

These are not indications of a civil unrest but an aging city. It’s an easy bet to win that if you are standing at any intersection in Manhattan you have at least one in your sight – this is how abundant they are. They are ugly and obstruct pedestrian traffic. New Yorkers get used to them but you don’t need to. Every building can be designed with permanent measures for general public protection while a work is performed on a façade.

Choice of low-maintenance materials like self-cleaning glass is a viable

way to limit the frequency of maintenance. However, such a glass would need

moving rain-water to clean its surface. Many architects design sloped glazing

almost flat, promoting water pounding and defeating the self-cleaning glass

purpose. |

Indications

The need for a dedicated façade access anchors and tie-offs typically arises unless all facades of the building are accessible by a portable off-the street equipment and unless the roofs are free from any fall hazard (e.g. fully surrounded by tall parapet walls). The choice (or lack thereof) of equipment and anchorage is up to the owner, as it’s mainly a financial dilemma of weighting the initial cost versus life cost. Smaller buildings inaccessible from any driveway (as is often a case with courtyards and monumental lobbies) may require also dedicated provisions for access (Figure #6).

There are boom lifts and truck cranes that can reach above 39.6m [130ft] available at steep rental cost. The interior facades frequently can be accessed by aerial platforms, providing the doors, elevators, and corridors on the way have sufficient size and capacity to allow for their transportation. (Figure #6)

However; there may be situations (over 300ft height) where permanent equipment is the only means of access to the façade. An architect should identify such a situation and provide a design solution.

Dedicated, permanent solutions are characterized by a higher initial cost and hard-to-calculate rate of return. How often will a building maintenance unit (BMU) be needed and for what duration?

Every project is different. Glass manufacturer require frequent washing of window glass (e.g. every three months) to keep it from free from corrosive residues. As-needed repairs may turn out to be required more often than initially expected.

The duration of work may extend beyond initial expectations. It helps to remember that even though the George Washington Bridge needs to be repainted only every two years, the repainting process takes the entire two years, and the suspended gantry underneath the bridge is operated on ongoing basis (according to a tourist guide).

Important long-term consideration is the downtime of crew performing the work. A frequent picture is a building with only two dedicated davit arms. Every time a scaffold finishes a drop, the crew needs to move the arms from one socket to another; as opposed to have two spare davit arms simultaneously installed on the next drop. Quick and constant façade access reduces both schedule and budget uncertainty due to the weather.

Somehow, the power is never there. A typical powered scaffold needs a three-phase 230V supply but the nearest electrical outlet is often located so far away that troubleshooting the energy outage takes hours. A dedicated, splash proof outlet and water bib should be available at strategic locations, serving roofs and facades.

Another important consideration is the ease of use. A worker who needs to detach and tie his/her lanyard over and over again is not only left without protection while doing so, but also spends time less productive than a worker who works on a building equipped with a monorail system and moves a trolley along the rail.

Figure #9.

Simple and effective permanent, self-powered, bucket system on a perimeter rail.

Wishful thinking

My perspective may be little skewed because I spent too much time on a wrong side of a wall. The older I get, the more I like dedicated, permanent house rigs, because they look more reliable and safer than parapet hooks. They are much more expensive than a frugal grid of anchors, but they provide a much safer and more comfortable access. However, there are some caveats.

Among dedicated solutions, the most economical solution is a single building maintenance unit (BMU). it requires a contiguous, dedicated perimeter of roof or parapet wall close enough at least one spot to the podium in such a way that it’s possible to park the platform with some access to and from a public road, so an average size truck may be loaded. (Figure #14).

The obstructions are typically of architectural character. In the past high-rise architects loved fragmented roofs: a flat piece here, a steep slope there, and yet a terrace over there… Today, the current fashion eliminates roofs; a curtain wall slopes back into a building instead. The courtyards among the podiums are glazed too, creating impenetrable and inaccessible zones that are usually marked by wildlife nests and thick deposits of dirt and debris.

All that entails is that the multimillion dollar BMU may serve only a fragment of a building, and an owner (or insurance company) would need to spend $5k a day for a rental of a 120 ton hydraulic crane anyway.

Another caveat is the shape of the building façade plan in violation of principle of ergonomics. Deep pockets and narrow recessions in a façade make not only swinging platforms access impractical or impossible but also out of human reach. This situation often results in construction defects and deferred maintenance.

A frequent picture is a repair or maintenance contractor installing a traditional swinging stage rig in front of a perfectly good BMU. Why? A house rig requires a skilled and certified operator which would either need to be permanently employed or temporarily hired by either the owner or a contractor. Also, a rig like this requires an annual inspection and maintenance, which might have been postponed by an owner.

A fall hazard may be created by the very fall arrest system created to prevent it. Davits located at the very edge of a roof that require a worker to approach them in order to install a façade fall arrest system but don’t allow for personal fall-arrest tie-in of a worker installing them are a good example. They should be protected by a secondary means of fall arrest.(Figure#11).

Another story. I was inspecting over 40 roofs of a community of low-rise, multi-family, residential buildings in Miami, FL. A 25ft, extended, portable ladder was the only means of access, there was no lifeline, no davits, nothing to protect one from a free fall. I was walking on one of them, while a flat portion of roof deck collapsed under my right foot. The deck turned out to be rotten from a prolonged water leakage. The low-rise buildings avoid the scrutiny reserved for taller buildings and are typically void of any safeguards, which one is accustomed to see in a high-rise construction. This makes them the most dangerous in my experience. It doesn’t make much difference to fall 25ft or 500ft – result is usually the same.

As the design industry shrinks and becomes more competitive than ever, many designers may find themselves walking on roofs and scaling ladders in a field. I can only hope that they foresee this possibility and provide a safe access to the walls and roofs while they are still in the design business.

Figure #10.

A segmented, interior gantry stored at the end of a barrel sloped glazing.

Figure #11.

A davit sleeve with access protected by a stainless steel guard.

Conclusion

In my experience the façade access is among items most often overlooked by designers. However, the need for access becomes acutely obvious in the early construction phase, and the necessary addition of window washing equipment comes as a late and unwelcome surprise that plays havoc with the design, the budget, and the construction schedule.

Figure #12.

Three BMUs serving a simple tower with a steep roof.

Figure #13.

A BMU serving the horizontal roof ridge.

Figure #14.

One of two BMUs serving the diagonal roof edges.

About the author

Karol Kazmierczak (Kaz), CDT, ASHRAE, NCARB, LEED AP, is the senior building science architect and the leader of the BEC Miami. He has 17 years of experience in building enclosure technical design, engineering, consulting, and inspection, with significant knowledge of curtain walls and architectural glass and a particular focus on thermodynamics. He can be contacted via e-mail at info@b-e-c.info.

|

|